From sprouting barley seeds to modern pregnancy care

In ancient Egypt, the earliest pregnancy test was women urinating on bags of wheat and barley seeds to see if they sprouted — a sprout was a positive test. (Fun fact — in the 60s, researchers actually validated the science behind this — and showed that this method predicted true positive pregnancies 70% of the time!)

For thousands of years, pregnancy and childbirth practices were based on tradition, expert opinion, and observation — but rarely on systematic testing of what actually worked.

Modern pregnancy care: what's behind the guidelines

Today's pregnancy care looks dramatically different: we have ultrasounds, genetic screening, and medications that save lives (and yes, of course, modernized pregnancy tests). Yet surprisingly, many standard practices still became "routine" the old-fashioned way — through professional consensus, experimentation, and biological plausibility rather than rigorous research.

Some of today’s most confident guidance, like folic acid supplementation preventing certain kinds of birth defects and low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention, rest on solid evidence from randomized trials. Others, like continuous fetal monitoring during labor or pre-labor cervical checks, became universal despite limited evidence they improve outcomes.

This pattern extends far beyond labor practices — for most medications and countless daily exposures during pregnancy, we lack rigorous evidence about safety and effectiveness. For example — can moms take melatonin while pregnant? What about medication for their chronic condition? Despite the fact that most women take at least one medication during pregnancy, fewer than 10% of the medications approved since 1980 — yes, 45 years ago — have adequate data demonstrating safety during pregnancy.

A brief history on women & pregnancy in clinical trials

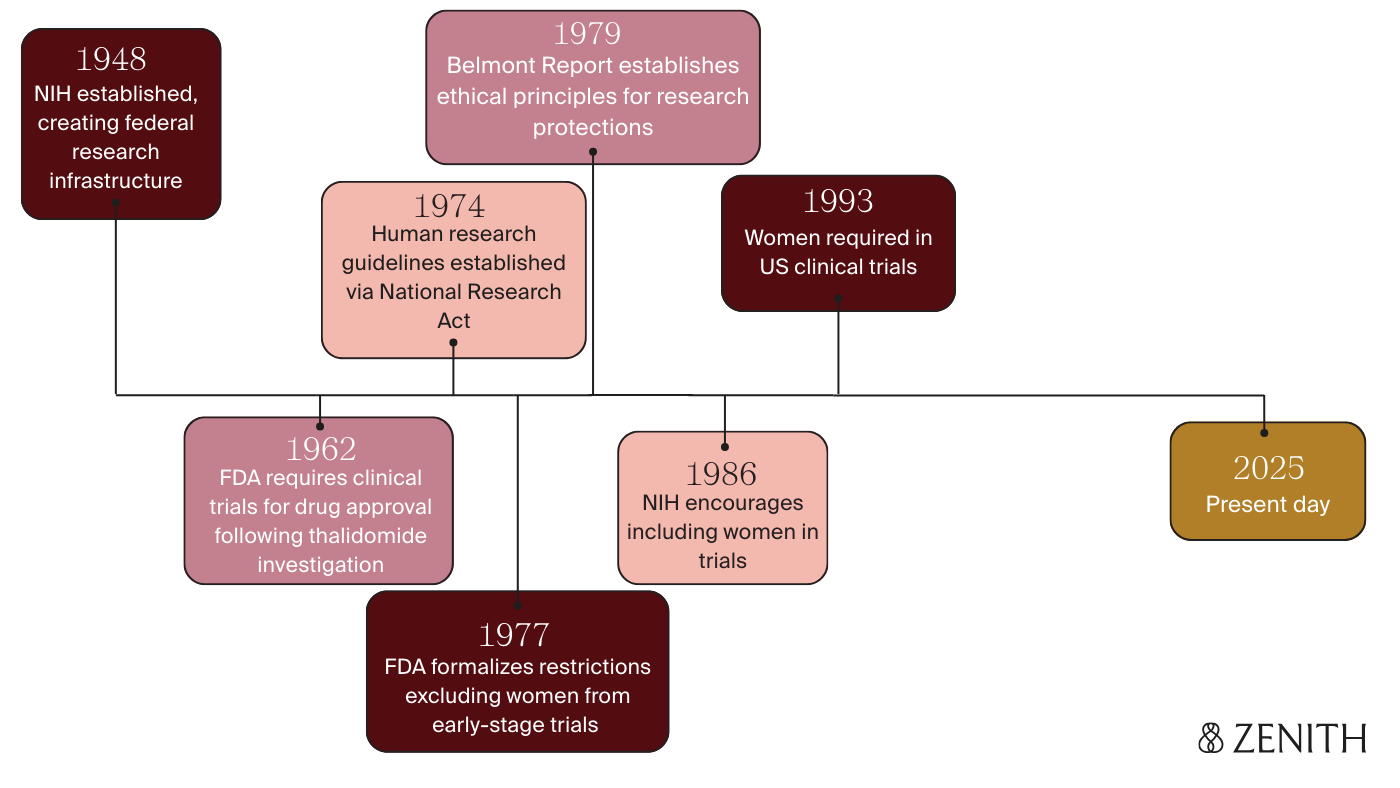

So how did we get here? Today, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are generally the gold standard for evaluating safety and effectiveness of medications, but it wasn’t actually until 1962 that the FDA began to require them for new drug approval.

This requirement was implemented largely in response to the thalidomide tragedy — a drug initially introduced in the 1950s to treat morning sickness, but which hadn’t undergone rigorous safety testing before its release. Women were prescribed the drug, unfortunately leading to the birth of over 10,000 babies worldwide with severe birth defects — as it ultimately took over 5 years to link the thalidomide exposures during pregnancy to these devastating outcomes and stop prescribing it.

In the aftermath, guidelines swung far in the opposite direction, and pregnant women (and often all women “of childbearing potential”) were systematically excluded from drug trials. FDA guidelines in 1977 defined this as "any premenopausal woman capable of becoming pregnant" — even those using contraceptives or whose husbands had been vasectomized.

It wasn’t until 1986 that the NIH encouraged researchers to include women in clinical studies, and the FDA eventually required it in 1993. Unfortunately, the precedent that had been set held back women’s health research for decades. Pregnant women still remain largely excluded today — with concerns cited related to fetal harm, legal liability, and ethics, as well as research regulations classifying them as a vulnerable population in need of special protection.

There’s a growing recognition among experts that excluding pregnant people may cause more harm than including them — after all, pregnant people take medications whether we study them or not. But we're still far from overcoming the regulatory and practical barriers to changing this standard. So how do we fill the gaps in pregnancy evidence, when traditional clinical trials aren't possible?

Observational research: learning from pregnancies in the real world

This is where observational research can provide immense value. Observational studies track and analyze what happens in the real world, without randomizing participants into groups that receive a treatment or a placebo. Doing research in this way requires careful study design: to ensure groups being compared are truly comparable, that the populations studied are representative of the broader population of interest, and that the results are statistically meaningful.

In our next blog installment, we’re exploring how observational research works: how researchers can answer causal questions without randomized controlled trials, and why conclusions from some observational studies are more trustworthy than others (and how to tell the difference).